Breath Orchestra is an ongoing series of sound, video, and participatory performance works rooted in the oral traditions and embodied breathing techniques of the Haenyeo, Jeju Island’s elderly women divers. The project unfolds through workshops, rehearsals, collective listening, and repeated enactments, where breath is practiced, shared, and learned as a form of living knowledge.

Yo-E Ryou, 숨 오케스트라 (Breath Orchestra), Act 1

5.1 channel sound installation, 10min 10sec., 2024

Yo-E Ryou, 숨 오케스트라 (Breath Orchestra), Act 2

4k video and 5.1 channel sound installation, 10min 10sec., 2024

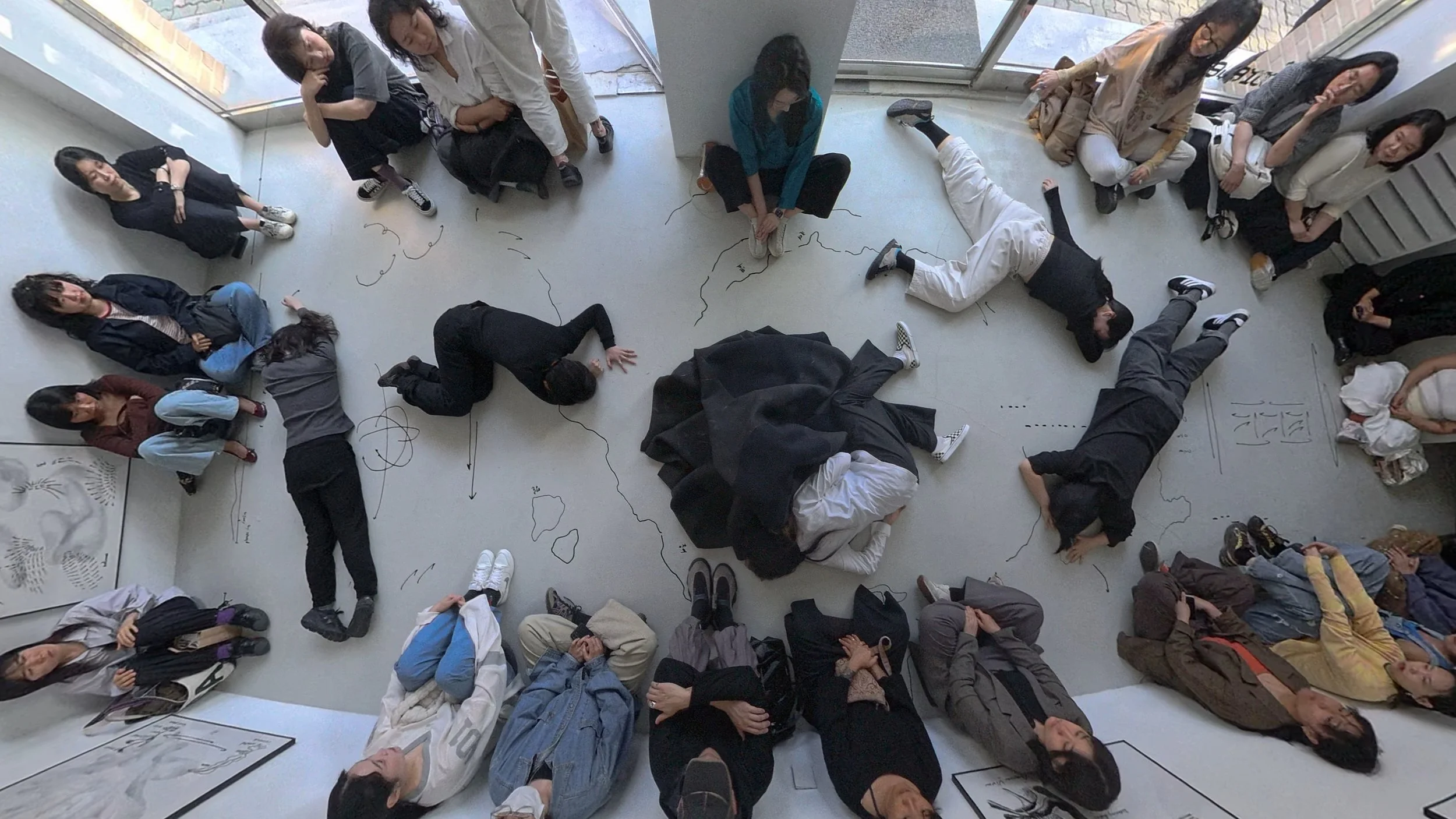

Yo-E Ryou, 숨 오케스트라 (Breath Orchestra), Act 3

performance, Forever Gallery, Seoul, April 20, 2025

Yo-E Ryou, 숨 오케스트라 (Breath Orchestra), Act 4

performance, Alternative Space LOOP, Seoul, July 25, 2025

Yo-E Ryou, 숨 오케스트라 (Breath Orchestra), Act 5-6

performance, WINDMILL, Seoul, September 26, 2025

-

The artist, having moved to Jeju and completed training at the Haenyeo school, weaves the sensory memories gained from the sea into visual, auditory, and tactile language while practicing diving with the neighbor Haenyeos. She learns the embodied language of water, passed down through spoken words and bodily interactions.

This project is being iterated in series, in multiple forms—sound installation, video, performance and workshop, originating from the realization that the Haenyeo’s sounds—filling up their breath before diving, the silence while submerged, the sound of emptying the breath when resurfacing ("sumbi sori"), and the subsequent catching of breath—are not merely physiological necessities but a language embodying the rhythm of life passed down through generations.

Children around the age of 10-12 years old, when Haenyeo traditionally started diving, form a breath orchestra of the sea, synchronizing their breathing alone, together. The project confronts the past, present, and future of Jeju island. The sounds of breathing with and emptying the water are individually and collectively heard and remembered through the body. The participants mimic and learn these sounds, internalizing Haenyeo’s diving routines and experiencing bodily movements and breath control. The community’s breaths are sometimes synchronized and sometimes individualized, immersing the audience in the physical and emotional space of the Jeju sea. These breaths intertwine with the surrounding sounds of the sea—waves, wind, and the ebb and flow of breath.

The silence in the moments of breath-holding symbolizes the literal act of diving and the time spent underwater, a space where life’s extremes converge. The alternating calm above water and dynamic activity below highlight the interplay of stillness and movement in Haenyeo's practice. This contrast captures the existence of the Haenyeo, reflecting their paradoxical daily life where intense activity meets profound tranquility. It explores the intersection of life and death, love and destruction, labor and play, pain and recovery. Experiencing their harmonious breathing with the water, the project conveys respect, awe, and mourning for the disappearance of the symbiotic relationship between the Haenyeo and the sea. It connects collective memory with individual identity.

Visitors are invited to listen, observe, and breathe together, encountering the language of water in the Haenyeo’s world in a sensory manner. The immersive space allows visitors to reflect on the rhythm of breathing and the connection to nature, providing a time to rediscover and share our innate connection to water.

Breath Orchestra is not only a tribute to the Haenyeo but also an exploration of how tradition meets modernity, how individual and collective identities are formed, and how knowledge is transmitted through physically soaked bodies. It contemplates how the wisdom of the past can influence the present and future, and the role of emotions and experiences that cannot be captured in words.

-

“Listening in wild places, we are audience to conversations in a language not our own."

— Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding SweetgrassA circle of young girls dressed in white are sitting on black rocks that lead into the deep blue sea. Consciously breathing with a sound of sseup—, they inhale deep into their bodies and hold their breath. After a moment of stillness, they exhale with a resonant sound, oompa—. Accompanied by sounds—haa—, hoo—, whee—, pah—, they expand their chest, close their eyes, and purse or relax their lips. When holding their breath, the silence reigns, but the fierce negotiation with breath connected to life is palpable. As the breath taken inside their lungs cannot be contained forever, they soon exhale deeply, releasing it back out. Each girl breathes in and out in her own rhythm. Although their eyes are closed, they listen to the breathing of the friends beside them, sensing each other's presence. The sound of another’s breathing becomes a sign, translating to “I am here,” “I am alive,” “I am okay.” They may not breathe in or out at the same time, but safety still depends on breathing together. They, thus, traverse the path that leads to the sea, walking in and out together. The girls’ ritualistic breathing on the rocks echoes the practices of Jeju Haenyeo, women divers who labor in the sea. In this oceanic realm, the haenyeo also swim and hold their breath. The undulating movements of the seawater and seaweed resemble the gestures of the haenyeo. Just as the tides shift the boundaries between sea and land, the haenyeo’s swimming and breathing blur the lines between inside and outside the water. The bodies of the haenyeo become bodies of water. The sounds of the haenyeo’s swimming merge with those of the girls’ breathing. Their gestures create sound, forming a tactile and resonant dialogue. The girls’ breathing becomes a way of preparing to enter the world of water, just like the haenyeo. The present of the Haenyeo and the future of the girls are connected through the act of breathing.

The space where humans, like other mammals, can breathe is a world filled with air. In this world, we can breathe without conscious effort, even when we are asleep or unconscious. So why are these girls practicing breathing on the rocks? They are learning how to breathe and exist in a new world—the world of water. Humans without gills cannot breathe in a world filled with water, but haenyeo can breathe while navigating the boundary between land and sea. Without relying on the scientific technologies revered by anthropocentric modern societies, the haenyeo know how to align their breath with life underwater. Their breath, nevertheless, hovers precariously between life and death, thus, the haenyeo practice must be mastered and embodied with their entire being. These girls are learning the breathing of the Haenyeo.

Breath Orchestra is a sequel to Yo-E Ryou's earlier work, Why I Swim. In Why I Swim, the artist sought, in her own words, to "unlearn" the act of swimming—a process aimed at sensing anew how to exist within the space of water. This "unlearning" of swimming naturally led to the "unlearning" of breathing, which brought forth this series of works, Breath Orchestra. It is because the gestures of swimming are rooted in the act of breathing inside and outside water. At the heart of both works lies a fundamental question of boundaries. How can bodies belonging to different worlds transcend those boundaries to communicate with one another? Yet, a deeper question emerges: are we humans even wiling to communicate with the bodies from other worlds?

Our society seems to lack ethical consideration for the haeneyo, just as it does for nonhuman beings. While the haenyeo culture is officially celebrated as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity that must be preserved, our society paradoxically prioritizes economic development that devastates the marine ecosystems, which is the foundation of haenyeo’s livelihood. This contradiction mirrors policies that actively exterminate endangered species of flora and fauna under the justification that they cause economic loss, even though human industrial activities have already propelled the Earth into the sixth mass extinction era due to climate change.

In these works, the artist deliberately avoids directly portraying the haenyeo, rejecting the objectification of haenyeo as pre-modern relics or their commodification as tourist attractions/commodities. Instead, the artist captures other bodies—her own and those of young girls—learning and embodying the gestures of haenyeo as a language of water. These gestures serve as a way to learn from and document the ecological and embodied practices of the haenyeo without exploiting their image.

After living abroad for over a decade, the artist settled in a small village on Jeju Island during the COVID-19 pandemic by chance, and there, she learned how to swim and breathe from the haenyeo. This way of moving through water was entirely different from the swimming techniques the artist had tried to learn—or failed to learn—while living on the mainland, particularly in urban environments. The haenyeo, who were deprived of any opportunity for formal education because they were daughters, were forced to earn a living by diving. They were not taught standardized swimming methods; instead, each haenyeo developed her own ways of swimming, diving, and breathing, or inherited techniques passed down from her mother and other senior haenyeo. Just as their bodies vary, so do their diving practices, yet none have been officially documented. Unlike most certified sports, which are systematized and standardized around Westernized adult male bodies, haenyeo techniques remain unique, diverse, and deeply personal.

Through her time with her haenyeo neighbors, the artist came to understand the vast gap between herself and the haenyeo, as if they inhabited entirely different worlds, although they existed in the same time and space. The world of standardized English and Korean language versus the world of Jeju Island language; the world of formal education versus the world of self-taught knowledge from nature; the world of those who breathe only on land versus those who breathe and communicate across the boundaries between water and land. Having spent a lifetime diving in the sea, the haenyeo have embodied the essence of water, mastering its breath and its language.

The artist comes to realize their breathing sounds not merely as physiological phenomena but as “a language that carries the rhythm of life passed down through generations.” Living alongside the haenyeo, she is drawn to interpret the breaths they inhale and exhale to understand this language of breath experienced with the entire body soaked in the sea. To do so, she must cross the boundary that divides the two worlds. Learning the art of muljil from the Haenyeo, the artist breaks away from the unconscious breathing patterns of modern urban life and explores a new way of breathing that bridges the worlds of water and land. This new understanding is documented within her own body and those of the young girls with whom she shares it.

Anthropologist Eduardo Kohn considers the gestures, sounds, and physical appearances of all living beings as signs—their language. Kohn argues that language is not limited to human language which mainly uses symbolic representation that sounds and meanings are arbitrarily connected, but also includes “iconic” signs that share likenesses of sounds and motions with what they represent and “indexical” signs that are in a relation with what they represent. All living beings evolve by interpreting and responding to one another’s signs—a process that is not merely biological but one of thought and communication. For Kohn, this sign process is what constitutes life itself. He writes, “because life is semiotic and semiosis is alive, it makes sense to treat both lives and thoughts as ‘living thoughts’”(How Forests Think, p. 78).

The haenyeo’s breaths can be understood as iconic signs that represent their bodies moving across the boundaries in and out of the water, as well as an embodied language that is felt, expressed, and interpreted through the senses. Unlike human language, breathing enables interspecies communication. Because most living beings on Earth breathe, this unspoken language becomes a universal medium to share thoughts without the need for translation. Just as the sound of a nearby companion’s breath provides reassurance, breath acts as a sign that brings affective understanding and mutual recognition.

Breathing, then, is fundamentally about relationships. If Why I Swim explored the body’s entanglement with the sea, Breath Orchestra expands this exploration to the relationships with beings who breathe inside as well as outside water. Breath, entering and exiting countless earthly beings, forms a shared materiality in diverse bodies. Feminist literary scholar Stacy Alaimo theorizes this interconnected embodiment as “transcorporeality.” When we inhale, oxygen from the air is absorbed into our bodies through the lungs. When we exhale, carbon dioxide produced within our bodies is released. unbeknownst to us, the carbon dioxide we exhale enters the breaths of trees, mosses, phytoplankton, and seaweed, becoming part of their bodies, while the oxygen they release flows into the bodies of animals like us. Through breath, we are intrinsicably connected to the diverse life forms of forests and oceans. The breath that sustains and animates our bodies also sustains theirs, weaving our bodies into the same web of materials, allowing us to think through this shared process of exchange.

We once breathed in the world of water. But upon leaving the amniotic fluid of our mother’s womb and entering the world outside of the water, we had to forget how to breathe underwater and learn to breathe in the air. For most, this transition between the old and new ways of breathing happens almost intuitively. Some newborns may need a helping hand, but many accomplish this "unlearning" and "learning" on their own. Yet, this doesn’t mean that we have completely forgotten how to breathe in water. Newborns and infants often feel comfortable in water and can swim instinctively. The artist points out that human lungs were once as large and developed as those of whales but diminished in function after humans moved out of the water, and the organs of Haenyeo who dive extensively may expand up to three times the size of the average human’s, partially regaining this lost lung capacity.

As the audience watches the girls breathe in this art work, they too begin to inhale, hold, and exhale, tracing the rhythm in their own cycle. The rhythm of breath—the language of water—passes from the haenyeo to the girls and from the girls to the audience. By meeting the body of water, the Haenyeo, the girls, and the audience learn to connect, interact, and communicate with water. They learn to breathe. They begin to understand the thoughts of the whales. Together, they together inhale with the sound of sseup—, and then pause. They exhale with resonant sounds of oompa—. Their breaths vibrate with sounds like haa—, hoo—, whee—, pah—.

—

The Language of Water, The Language of Haenyeo

Gowoon Noh (Cultural Anthropologist, Chonnam National University) -

제주에 와서 나는 물을 만난다. 삼십 년이 넘도록 터득하지 못했던 헤엄치는 법을 배우며 몸으로만 이해할 수 있는 언어를 다시 익히기 시작한다. 말하는 법, 듣는 법, 쓰는 법, 읽는 법도 다시 체화해 나간다. 한동안 수면 위를 유영하기만 하던 나는 어느새 물 속으로 점점 스며든다. 옆집 해녀 삼춘 물마중을 나가고, 해녀 학교에 다니며 잠수하는 법을 터득한다. 물에 젖은 몸으로 전해지는 언어, 몸에서 몸으로, 입말로 전해지는 물과 몸의 언어를 만난다. 물 속에서 들리는 소리에 귀 기울이기 시작한다. 나의 몸과 물의 몸, 이웃 해녀 할머니와 바다의 몸이 서로 얽혀 헤엄에 대한 의미를 찾아간다. 잃어버렸던 언어를 다시 배워본다.

이번 숨 오케스트라 작업은 이웃 해녀들과 물질 연습을 하며 바닷속에서 얻은 감각적 인상을 어떻게 담을 수 있을까라는 질문에서 시작된다. 해녀들이 잠수 전 숨을 고르는 소리, 잠수하는 동안의 정적, 잠수 후 수면으로 올라올 때 내뱉는 숨소리 "숨비소리"와 다시 숨을 고르는 소리가 반복되는 것은 단순한 생리적 필요가 아니라 세대를 거쳐 전해지는 삶의 리듬을 담은 언어이다. 나는 섬과 육지 사이를, 동서양의 세대 차이를 헤엄치며 당신의 언어와 나의 언어가 연결되기를 바라며 손 안에 담기 어려운 바닷속 이야기를 시각적, 청각적, 촉각적 언어로 엮어본다. 한 언어를 다른 언어로 번역하는 과정에 대해 사유한다. 원어와 번역어, 출발어(source language)와 도착어(target language)의 관계처럼 물의 언어는 어디에서 출발해 어디로 도착하는 것일까 생각해본다.

학교 대신 바다로 향하던 10살즈음의 아이들과 제주 바다에서 숨 오케스트라를 이루어 함께 호흡을 맞춰본다. 과거와 현재, 미래와 마주한다. 물과 함께 숨을 쉬고 비우는 소리를 각자 또 함께 몸으로 듣고, 기억해본다. 따라 말해보고, 배워본다. 내가 배운 해녀들의 잠수법과 호흡법을 아이들이 보고 따라한다. 각자의 몸에서 다르게 동기화된 움직임이 스며나온다. 공동체의 숨소리는 때로는 함께, 때로는 개별적으로 들리며 청중을 제주 바다의 물리적, 감정적 공간으로 몰입시킨다. 바다의 주변 소리—파도 소리, 바람 소리, 물 안팎을 오가는 적막의 소리—와 어우러진다.

숨을 참는 순간의 정적은 잠수라는 문자 그대로의 행위를 넘어서, 물 속에서 보내는 시간 자체를 상징하며, 삶의 경계가 만나는 공간이 된다. 물 위의 고요함과 물 속의 역동적 활동을 오가며 해녀의 실천에는 정지와 움직임이 공존한다. 이러한 대조에서 해녀의 존재를 포착하며, 강렬한 활동과 깊은 고요함이 교차하는 역설적인 해녀의 일상을 반영한다. 삶과 죽음의 경계, 사랑과 파괴, 일과 놀이, 고통과 회복 등 모순과 모순이 만나는 교차점을 탐구한다. 물과 조화를 이루며 호흡하는 모습을 상상하며 해녀와 바다의 공생적 관계에 대한 존경과 경이로움, 사라짐에 대한 애도를 담는다. 집단적 기억과 개별적 정체성을 연결한다.

함께 듣고, 보고, 호흡하며 해녀들의 세계를 감각적으로 기억하는 물의 언어를 새로이, 또는 다시, 만난다. 자연의 호흡과 리듬으로 연결되는 몰입의 소통을 경험하고, 우리 모두가 가진 물과의 연결성을 되새겨본다.

숨 오케스트라는 해녀들에 대한 헌사일 뿐만 아니라 전통과 현대가 만나는 방식, 개인과 집단의 정체성이 형성되는 방식을 탐구한다. 물에 젖은 몸에서 몸으로 연결되어 전해지는 과정을 통해 과거의 지혜가 현재와 미래에 어떻게 영향을 미칠 수 있는지, 글자로 담을 수 없는 마음, 언어화 될 수 없는 경험, 몸으로만 이해할 수 있는 언어를 헤아려본다. 투명한 말과 물의 시차를 오가며 받아 들여졌다가, 튕겨 나오기를 반복한다.

-

“야생의 장소에서 귀를 기울이면 우리 것이 아닌 언어로 이루어지는 대화의 관객이 된다.” (로빈 윌 키머러, 『향모를 땋으며』80쪽)

숨 오케스트라, Act 2:

흰 옷을 입은 어린 소녀들이 깊고 푸른 바다로 이어지는 검은 바위에 동그랗게 모여 앉아 의식적으로 숨을 쉰다. 스읍—하는 소리와 함께몸 속 깊이 숨을 들이마신 후 숨을 참는다. 잠깐 동안의 정적 후 음파—하는 소리를 내며 숨을 내쉰다. 하아—, 후우—, 휘이—, 파아— 하는소리와 함께 가슴을 부풀리고, 눈을 감고, 입을 오므리거나 다문다. 숨을 참을 때는 아무 소리도 나지 않아 고요하지만, 몸 안에 들어온 숨을영원히 담아둘 수는 없기에 그 다음 차례의 내쉬기를 준비한다. 저마다 다른 리듬으로 숨을 들이마시고 내뱉는다. 눈을 감고 있지만 옆 친구들의 숨소리를 들으며 서로의 존재를 느낀다. 상대의 숨쉬는 소리는 기호가 되어 ‘나 여기에 있어’, ‘나 살아 있어’, ‘나 괜찮아’ 라고 번역된다. 동시에 숨을 들이마시고 내쉬지는 않지만 함께 숨을 쉬어야 안전하다. 그래서 소녀들은 바다로 이어진 길을 함께 걸어 들어가고 나온다. 소녀들이 숨쉬기를 나누는 바위는 제주 해녀들이 물질을 하는 바다와 겹쳐진다. 바다가 된 공간에서 해녀들이 헤엄치며 숨을 참는다. 바닷물과 해조류의 일렁거림이 해녀들의 몸짓과 닮았다. 밀물과 썰물이 바다와 땅의 경계를 이리 저리 옮겨 놓듯이, 해녀들의 헤엄과 숨은 물 안과 밖의 경계를 흐트러뜨린다. 해녀의 몸은 물의 몸이 된다. 해녀들의 헤엄 소리와 소녀들의 숨소리가 합쳐진다. 그들의 몸짓은 소리를 내며접촉하고 소통한다. 소녀들의 숨쉬기는 해녀들처럼 물의 세계에 진입하기 위함이다. 해녀들의 지금과 소녀들의 나중이 숨쉬기로 연결된다.

포유류 동물인 인간이 숨을 쉴 수 있는 공간은 공기로 가득 찬 세계이다. 이 세계에서 우리는 의식하지 않아도 숨을 쉴 수 있기에 잠을 잘때도, 정신을 잃었을 때도 호흡한다. 그런데 이 소녀들은 왜 바위 위에서 숨쉬기를 연습하고 있을까? 이들은 새로운 세계, 물의 세계에서 숨쉬며 존재하는 법을 배우는 중이다. 아가미가 없는 인간은 물로 가득 찬 세계에서는 숨을 쉴 수 없지만, 해녀들은 물과 땅의 경계를 오가며숨을 쉰다. 그들은 인간중심주의적 근대 사회가 숭배하는 과학 기술에 의존하지 않고도 물 속 생물들과 호흡을 맞출 수 있다. 하지만 그들의숨쉬기는 또한 삶과 죽음의 경계를 아슬아슬하게 떠다닌다. 그래서 온몸으로 배우고 터득하지 않으면 안된다. 소녀들은 해녀들의 숨쉬기를배우고 있다.

이 작품은 제목에서도 알려주듯이, 요이 작가의 이전 작품인 숨 오케스트라, Act 1의 후속작이다. Act 1에서는 작가의 표현대로 헤엄치기의 ‘언러닝’을 수행하고자 했는데, 물의 공간에서 존재하는 법을 새롭게 감각하려는 것이었다. 헤엄치기의 ‘언러닝’은 숨쉬기의 ‘언러닝’을이끌었고, 숨 오케스트라, Act 2를 낳았다. 헤엄치는 몸짓은 물 안팎으로 숨을 통하고 참는 몸짓을 바탕으로 하여 이루어지기 때문이다. 두작품의 밑바탕에는 경계에 대한 질문이 있다. 서로 다른 세계에 속한 몸들은 어떻게 그 경계를 넘어서 소통할 수 있을까? 그런데 우리는 다른 세계의 몸들과 소통하려는 마음을 가지고 있는가?

해녀의 세계는 비인간 존재들의 세계처럼 윤리적으로 다루어지지 않아도 된다고 여겨지는 것 같다. 공식적으로는 보존해야 할 세계무형문화유산으로서 해녀 문화를 추앙하면서도 해녀들의 삶의 기반이 되는 해양 생태계를 파괴하는 경제 개발을 최우선순위에 두는 모순적인우리 사회에서 해녀들의 헤엄과 숨, 그들의 삶의 방식은 존중되지 않는다. 인류의 산업 활동이 가져온 기후변화 때문에 지구는 이미 제 6대생물 대멸종 시대에 들어섰지만, 경제적 손실을 일으킨다며 멸종위기종 동식물을 박멸하는 정책을 펼치는 것과 같다. 작가는 이 작품들에서 해녀의 모습을 거의 담지 않았는데, 전근대적 존재로 박제되거나 관광상품으로 대상화되어 유통되는 해녀의 이미지를 거부하기 때문이다. 대신에 작가는 해녀의 몸짓을 물의 언어로서 배우고 기록하는 다른 몸들을, 자신과 소녀들의 몸의 움직임을 작품에 담았다.

해외에서 십여 년을 지내다 코로나19 팬데믹 시기에 우연히 제주도의 한 작은 마을에 정주하게 된 작가는 해녀 삼촌들에게서 바다에서 헤엄치고 숨쉬는 법을 배우게 된다. 육지, 특히 도시에서만 살아온 작가가 배웠거나 배우지 못했던 수영법과는 전혀 다른 방식이었다. 해녀 삼촌들은 딸이라서 정규 교육의 기회를 박탈당하고 물질을 하여 돈을 벌도록 강요당했기에 표준화된 수영을 배우지 못했다. 그들은 각자 자신만의 헤엄, 잠수, 숨쉬기 방법을 터득했거나 선배 해녀들의 방법을 전수 받았다. 해녀의 몸이 다양한 만큼 그들의 잠수법도 다양하지만, 공식적으로 기록된 적은 없다. 서구화된 성인 남성의 몸에 맞춰진 공식화된 수영법이 아니기 때문이다. 작가는 같은 시공간에 존재하지만전혀 다른 세계에서 살아가는 것 같은 자신과 해녀 삼촌들 사이의 간극을 깨닫는다. 영어와 서울말의 세계와 제주말의 세계, 국가가 인정하는 정규 교육을 받은 자의 세계와 자연에서 스스로 지식을 터득한 자의 세계, 땅 위에서만 숨쉬며 소통하는 존재들의 세계와 이를 물 안과밖을 넘나들며 행하는 존재들의 세계. 평생 물질을 하며 바다에서 지낸 세월 만큼 그들은 물의 몸을 가지고 있기에 물의 숨, 물의 언어를 할줄 알았다. 작가는 해녀들의 숨쉬기와 숨소리는 단순한 생리 현상이 아니라 “세대를 거쳐 전해지는 삶의 리듬을 담은 언어라는 것을” 깨달았다고 말한다. 해녀들과 함께 살면서 작가는 그들이 바다에서 몸의 모든 감각으로 들이마시고 내쉬는 숨을 해석하고 싶어졌다. 그렇게 하려면 두 세계를 나누는 경계를 넘어서야 한다. 해녀 삼촌들에게서 물질을 배우는 작가는 현대 도시의 무의식적 숨쉬기 방법에서 빠져나와물의 세계와 땅의 세계를 연결하며 새롭게 숨쉬는 방법을 탐구한다. 그리고 그것을 어린 소녀들과 자신의 몸 안에 기록한다.

문화인류학자 에두와르도 콘은 모든 생물들의 몸짓, 소리, 신체의 모습을 기호로 간주하고, 이를 그 생물들의 언어로 본다. 콘은 어떤 소리와 의미가 임의적으로 연결되면서 언어를 이루는, 즉 상징을 주로 사용하는 인간의 언어뿐 아니라 표상하려는 사물과 유사한 소리나 동작을 나타내는 기호로 된 ‘아이콘적’ 표상 양식과 표상하려는 사물과 관련성 있는 기호로 이루어진 ‘인덱스적’ 표상 양식도 언어로 보아야 한다고 주장한다. 모든 생물은 서로의 몸짓, 소리, 신체의 모습에 서로 반응하면서 진화해 왔는데, 이는 단지 생물학적 반응이 아니라 서로의기호를 해석하며 사고해 온 과정의 결과인 것이다. 콘은 이 과정이 생명을 구성한다고 본다. 그는 “생명은 기호적이며 기호작용은 살아있기때문에 생명과 사고 모두를 ‘살아있는 사고’로 다루”어야 한다고 본다(에두와르도 콘, 『숲은 생각한다』139쪽). 해녀들의 숨은 물 안팎을넘나드는 몸짓을 표상하는 아이콘적 기호이며, 몸의 감각을 통해 표현하고 느끼고 해석하는 언어이다. 인간의 언어와 달리 숨쉬기는 생물종을 넘어선 소통을 가능하게 한다. 지구에서 살아가는 대부분의 생물은 숨을 쉬기에 번역하지 않아도 서로 소통이 가능한 언어를 통해 생각을 나눈다. 옆에서 숨쉬는 짝의 숨소리에 안심하듯이, 숨은 정동을 불러 일으키면서 서로의 존재를 이해하게 한다.

그렇다면 숨쉬기는 관계에 관한 것이다. 숨 오케스트라 Act 1의 헤엄치기가 몸과 바다가 얽히면서 맺어가는 관계를 보여줬다면, Act 2의숨쉬기는 함께 숨쉬는 물 안팎의 존재들과의 관계로 그 범위를 확장한다. 숨은 인간을 포함한 수많은 지구 존재들의 몸을 들어갔다 나왔다하면서 같은 물질로 서로 다른 몸들을 이룬다. 페미니스트 영문학자 스테이시 앨러이모는 이를 ‘횡단신체성’이라고 이론화했다. 코로 숨을들이 마시면 공기 중의 산소가 폐를 거쳐 몸에 흡수된다. 숨을 내쉬면 몸 속에서 생성된 이산화탄소가 빠져 나간다. 우리도 모르는 사이에호흡하는 동안 우리 몸을 빠져나간 이산화탄소는 나무와 이끼와 식물성 플랑크톤과 우뭇가사리의 숨을 따라 그들의 몸 속으로 들어가고, 그들이 내뱉은 산소는 우리와 같은 동물의 몸 속으로 들어온다. 우리는 숲과 바다의 다른 생물들과 숨으로 연결되어 있다. 우리의 몸에 생기를 불어넣는 숨은 그들의 몸에도 생기를 불어 넣으며, 우리의 몸들을 같은 물질로 이루며 사고하게 한다.

우리도 물의 세계에서 숨쉬었던 적이 있다. 하지만 어머니 뱃속의 양수를 떠나 공기의 세계로 진입하는 순간 우리는 물 속에서 숨쉬던 방법을 잊어야 했고, 물 밖 세계의 숨쉬기를 배워야 했다. 그 순간 다른 이의 도움 어린 손길이 필요한 아기도 있지만 거의 스스로 이전 숨쉬는방법의 ‘언러닝’과 새로운 숨쉬기의 ‘러닝’을 이루어 낸다. 그렇다고 물 속에서 숨쉬는 법을 영원히 잊어버린 것은 아니다. 태어난 지 얼마안된 아기들은 물을 편안해 하고 가르쳐주지 않아도 수영을 곧잘 한다. 작가는 원래 인간의 폐는 고래과 포유류 동물처럼 크고 잘 발달해 있었는데 물에서 나오면서 퇴화했다고 말하고, 잠수를 오래 한 해녀의 장기가 일반인보다 3배씩 더 커지기도 하면서 폐의 기능을 회복하기도한다고 알려 준다. 어린 소녀들의 숨쉬기를 담은 작품을 보면서 관객들도 숨을 들이마시고 참고 내쉬어 본다. 해녀들의 숨은 소녀들에게, 소녀들의 숨은 관객들에게 전이된다. 물이라는 몸을 만난 해녀들, 소녀들, 관객들은 물과 접촉하고, 교류하고, 소통하면서 물의 언어를 배운다. 숨을 배운다. 고래의 생각을 이해한다. 이들은 함께 스읍—하면서 숨을 들이마신 후 멈춘다. 음파—하는 소리를 내며 숨을 내쉰다. 하아—, 후우—, 휘이—, 파아— 하며 숨을 쉰다.

Breath Orchestra, Act 1 (installation view as part of the exhibition, Life on Earth: Art and Ecofeminism, curated by Catherine Taft), The Brick, Los Angeles, US

Breath Orchestra, Act 1-2 (installation view as part of the exhibition, Language of the Soul, curated by Yumin Kim), Jeju gallery, Seoul, Korea

숨 오케스트라 (Breath Orchestra), Act 3, Performance, Forever Gallery, Seoul, April 20, 2025

숨 오케스트라 (Breath Orchestra), Act 4, Performance, Alternative Space LOOP, Seoul, July 25, 2025

숨 오케스트라 (Breath Orchestra), Act 5, Performance, Han River Tunnel, Seoul, September 26, 2025

숨 오케스트라 (Breath Orchestra), Act 6, Performance, Windmill, Seoul, September 26, 2025